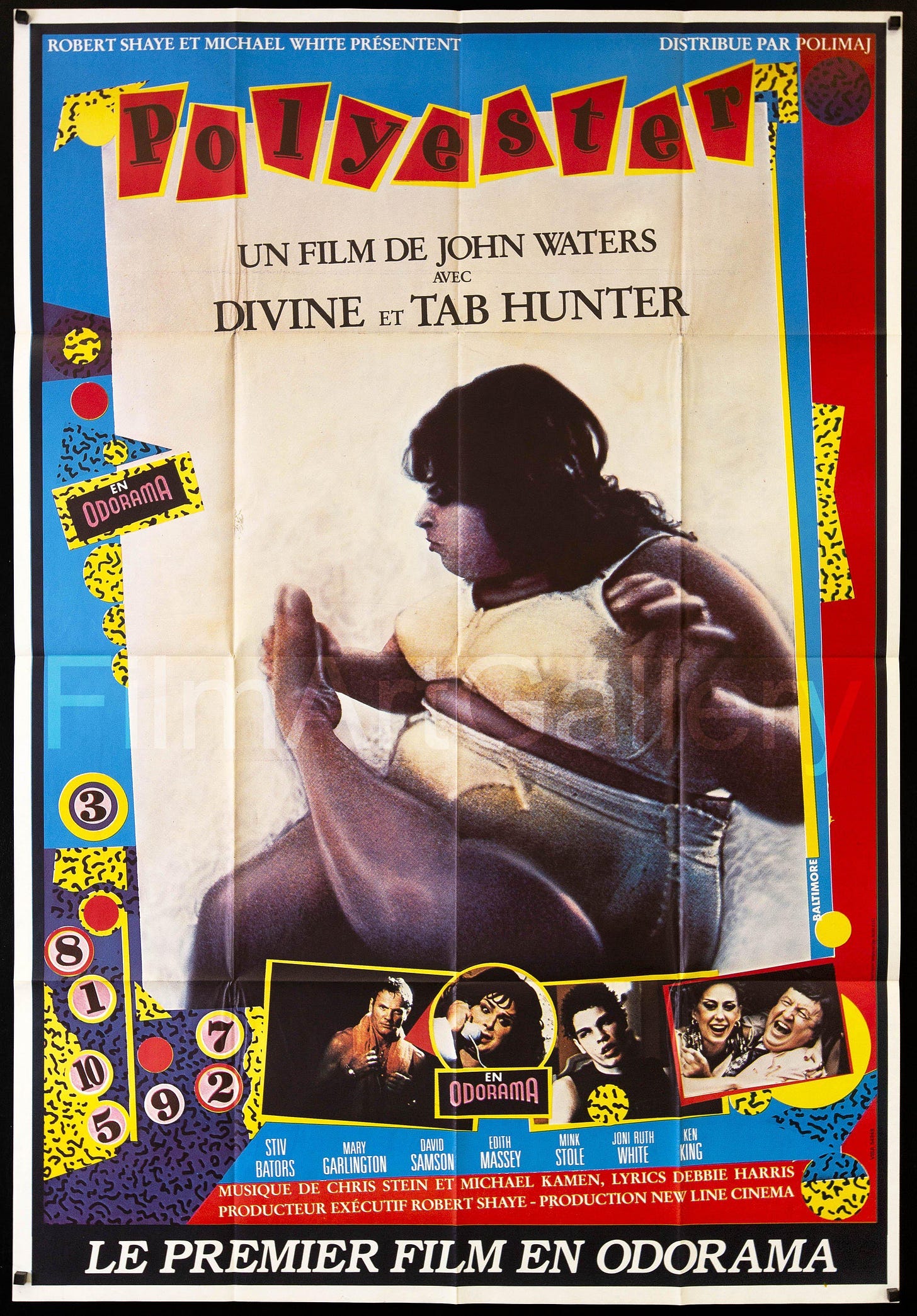

Polyester

Exploring the concept of family in John Waters 1981 film.

“I never talk about politics in my movies, because you don’t want to date them. You want your movies to play in 30 years.”

—John Waters

One of the things I enjoy about experiencing multiple works by an artist is watching common themes emerge. The recurring theme John Waters’ oeuvre is family. That is, if families were made up of murderous, backstabbing, perverts. And they are. Rather than hide behind a facade of social decency, Waters’ characters wear those traits on their sleeves. He is consistently subverting the family institution and white American sensibilities.

Casting a drag queen as a matriarch would be enough to offend the sensibilities of straight America. Divine is no ordinary drag queen. Divine is larger than life, a force of nature.

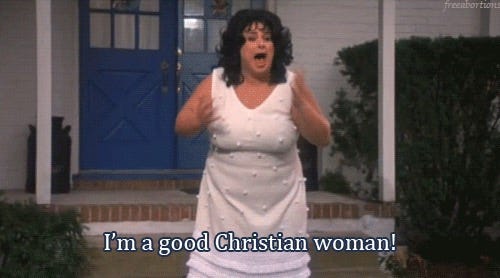

Francine Fishpaw wants nothing more than to be an upstanding, Christian housewife nestled in the suburbs. Unfortunately, her philandering husband runs a porn theater. Their home is under protest by religious groups. Her son is a serial stomper of ladies’ feet strung out on angel dust. Her daughter is in love with the local punk ass bad boy and she can’t wait to get an abortion. As her world crumbles, Francine does as well, becoming a compulsive eater and alcoholic.

Francine is nowhere near the vile terror that Divine’s other characters. Where characters like Lady Divine (Multiple Maniac) and Dawn Davenport (Female Trouble) are likely to go on such an offensive that the military called in to put them down, Francine is the voice of reason. However, she is just as ostentatious. Noise comes naturally to Divine (the actor). When Francine expresses disappointment in her husband for running an X-rated theater and basking in the populating of Christians protesting his home, it is the loudest disappointed housewife. When she takes to drink and becomes a shut-in, her house is a colorful disaster of bottles and garbage: discarded brands and articles of filth littering the floors and furniture. Babs Johnson (Pink Flamingos) wouldn’t hesitate to murder her enemies. Francine is nearly committed by those who wish to steal her money. And believe me, no one weeps themselves to shrill insanity like Divine playing Francine Fishpaw.

A protest is a means of inconveniencing or shaming a target into change. Elmer Fishpaw feels neither inconvenience nor shame upon seeing the anti-porn protestors outside his home. Elmer takes this opportunity to call the local news in hopes the bad publicity will drive business into his porn theater. On the news segment, we see men leaving the theater covering their faces to avoid the cameras stationed outside. There have been puritanical anti-porn crusaders for decades. Likewise, there have been viewers of pornography ashamed not of watching it but of being exposed as someone who’s watched it. For most men, pornography consumption is a solitary act. Most men don’t run porn theaters and prefer to separate work from their family life. Elmer is not one of those men. He welcomes the attention right to his doorstep.

No doubt Waters the protestors in Polyester were a commentary on attempts to censor his previous works. Notoriety only increased his fame.

Abortion has always been a contentious issue. On the heels of Roe v. Wade, I’d have to image it was even more sensitive. Fishpaw daughter Lu-Lu, played by Mary Garlington, owns the hilariously meme-able line “I’m getting an abortion and I can’t wait!” It’s a line that would still rile the anti-choice crowd today. Culture hasn’t progressed much since 1981. A rational person wants their fears to be false to guarantee a measure of safety in their world. The myth of the recreational abortion is one conservatives fear but want deeply to be true, just to prove they were right all along.

I would be remiss to not give props to Dreamlander mainstay Edith Massey, playing a newly rich former maid and true friend to Francine. She plays the debutant to perfection: a lavish, come what may free-spirited attitude toward life because there is always money. After Divine, Massey is always the biggest hit in Waters’ films. One gets the impression his Dreamlanders were more family than theater troupe.

In queer spaces there is the concept of the found family: individuals disowned—or simply disapproved, disavowed in some “love the sinner, hate the sin” nonsense—by their birth families, who discover and cluster together with similarly cast out non-heteronormative individuals to form new makeshift families. Perhaps that is why Polyester especially has such staying power. In typical Waters fashion the film lampoons American cultural norms, but it does so in a way that queer people can see the hypocrisy of their own families reflected. These are in-jokes for the out crowd. Polyester is also distinct from earlier films like Pink Flamingos in that it retains the in-your-face punk rock humor while being palatable for a wider audience. There are no gaping assholes, dogshit eating, or lobster rapes in this one, folks. Over 40 years later, it still plays.

When John Waters says he doesn’t talk politics in his movies, he isn’t lying. He never explicitly calls out a politician or contemporary political discussion. He does, however, address political issues. The Fishpaw’s are The Brady Bunch with the mask off. They are America’s flaws personified. Truth in satire. The housewife whose only currency is social value with other housewives. The daughter desperate to rebel who finds herself pregnant. Sex-crazed, smut peddling, money hungry men in a culture that tells them to get paid any way they can. These are all political issues. These are not mere discussions in his movies. These are the threads holding the entire tapestry together. Of course he would use the family—this pillar of American society—as ground zero for tackling these issues. The Fishpaws are exactly what American families see in the mirror, if only they open their eyes.